He had thought that to pray was to talk; he learned that to pray is not only to keep silent, but to listen.

- Søren Kierkegaard

I think I was in college when I first realized that prayers did not need to be words. I learned that I don't have to come up with words to say that sound right, or fit the situation, or that might seem correct. There is no correct or perfect way, it's about drawing close. This was a huge relief for me, as someone who was previously afraid to pray out loud in groups because I worried I wouldn't have the right words to say.

Prayer can be a sigh and deep breath. Prayer can be a glance up to the clouds in thanks. Prayer can be a 30 second moment with closed eyes in silence, listening. Prayer can be a word of blessing to another person. Prayer can be one word, said internally in a meditative (almost chant) within yourself. Focus on the word "grace" or the name "Jesus" for three minutes and you will come out of those minutes in a completely different frame of mind. A mind focused on Jesus has a way of steering you into the centered place best to live into the closeness to God.

Today is Ash Wednesday. We are entering the season of Lent - a 40 day journey through a period preceding the greatest gift of love but until then, this season is usually viewed from the world around us as a darkened, depressing, restrictive (requiring us to give up something) season. And it is true, we do travel through a time of focusing on the suffering. The dark, dusty things of life come up.

Dust to dust.

Do we forget that we came from dust? We focus quite a lot on the "to dust" part as we deal with death and suffering in our lives. No escaping this fact of our lives, so why not meditate on how much of a gift it is that we have limited time? Do you think it's a gift to have a finite amount of time here, or would you rather have an earthy life that spans centuries?

Grace upon grace.

Going ahead before us, the path is formed in grace, shaping the space we go into. We have nothing to fear because grace is going before us, preparing our way. Jesus has already formed the way ahead of us, in His harrowing of hell clearing the path, opening all the doors through the dark places so that light can leak in and we can follow.

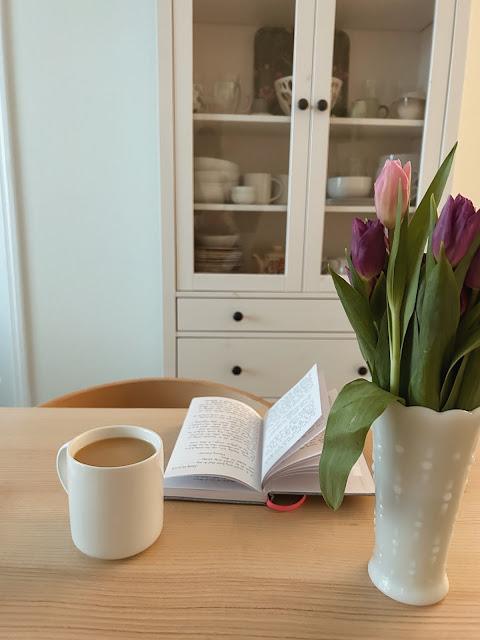

My tea cup is not empty, it is the space of grace, waiting to be filled with a moment of prayer.